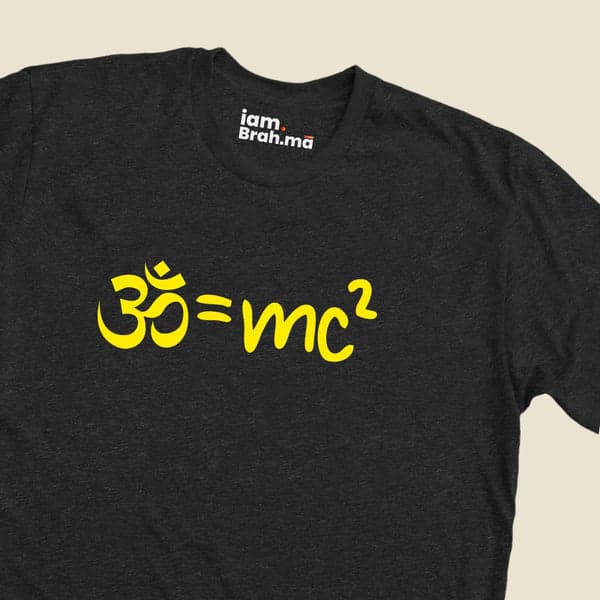

Finding the Brahma Within Me!

The impression of Brahma, when evaluated from the viewpoint of intellect, is a conception, but it is concretely true for those who have the precise vision to see it.

The Philosophy of Brahma

My understanding of Brahma through the philosophic writing is very scanty, I may be false when I indicate that this is just a philosophic conversation about the Upanishads in English, but, at any pace, the absence of kindness and honor showed in it for these some of the broadly spiritual and sacred words that have ever originated from the human mind, is incredible. However multiple symbolical representations utilized in the Upanishads can barely be comprehended today, or are certain to be inaccurately comprehended, still, the information as incorporated in these, like some infinite source of light, illuminating and vitalizing the spiritual mind of India. They are not correlated with any specific faith, but they have the extent of a common soil that can replenish with living sap all faiths which have any sacred purpose hidden at their foundation, or evident in their fruit and foliage.

Faiths, which have their various perspectives, each assert them for their support.

The Upanishadic Context

This has been credible because the Upanishads are based not upon theological wisdom, but on an understanding of spiritual life. And life is not opinionated; in its restraining forces are harmonized ideas of non-dualism and dualism, the infinite and the finite, do not prohibit each other. Moreover, the Upaniṣads do not exemplify the spiritual understanding of anyone’s extraordinary soul, but of an incredible age of enlightenment which has a complicated and combined representation, like that of the starry world. Several creeds may discover their sustenance from them, but can never establish sectarian barriers around them; generations of men in our nation, no very students of philosophy, but seekers of life’s fulfillment, may make abiding use of the texts, but can never deplete them of their freshness of meaning.

For such men, the Upanishad concepts are not completely conceptual, like those belonging to the region of pure logic and reasoning. They are substantial, like all truths realized through life. The impression of Brahma, when evaluated from the viewpoint of intellect, is a conception, but it is concretely true for those who have the precise vision to see it.

Cannot the exact thing be explained about light itself to men who may be some mischance live all through their lives in an underground world cut off from the sun’s lights? They must know that words can never explain to them what light is, and the mind, through its deducing ability, can never actually comprehend how one must have an immediate vision to realize it secretly and be delighted and free from fear.

We always hear the criticism that the Brahma of the Upaniṣhads is interpreted to us largely as a pile of negations. Are we not steered to take the exact course ourselves when a blind man inquires for an explanation of light? Have we not to explain in such a case that light has neither sound, nor smell, nor shape, nor weight, nor resistance, nor can it be recognized through any method of analysis? Of course, it can be seen; but what is the use of explaining this to one who has no eyes? He may take that statement on belief without understanding in the least what it suggests, or may altogether deny it, even doubting in us some abnormality.

Does the certainty of the fact that a blind man has lost the perfect growth of what should be natural about his eyesight depend for its evidence upon the truth that a substantial number of men are not blind? The very first thing which unexpectedly muffed into the possession of its eyesight had the freedom to affirm that light was a reality. In the human world there may be quite a few who have their sacred eyes open, but, in spite of the numerical majority of those who cannot see, their want of sight must not be illustrated as an indication of the dissolution of light.

Satyam and Anandam

In the Upaniṣhads we discover the note of fact about the sacred meaning of reality. In the very paradoxical nature of the argument that we can never know Brahma, but can realize the presence of Him, there lies the power of belief that comes from subjective experience. They aver that through our pleasure we know the endless truth, for the test by which fact is comprehended is joy. Thus in the Upanishads, Satyam and Anandam are one. Does not this belief harmonize with our everyday incidents?

The self of mine that restricts my validity within me constrains me to a narrow idea of my individuality. When through some great experience I exceed this boundary I discover pleasure. The pessimistic existence of the vanishing of the walls of self has nothing in itself that is wonderful. But my pleasure verifies that the disappearance of self brings me into sense with an amazing optimistic truth whose nature is infinitude.

...